Interview: Frederike Doffin & Cameron Middleton

Cameron: We wanted to have someone speak from the Movement, Mind, and Ecology Masters, but I particularly wanted to talk to you because we used to be neighbors, and I saw you developing the ideas for your thesis over time. Can you tell me more about how you came to the idea of transitioning ecological grief through the body?

Frederike: Um, yes, I think the fact that I worked with grief was because I felt a need in my own body to process grief. I have the feeling it’s part of my own healing journey, and I felt a need to commit to working with ecological grief in parallel. And I think in the whole project, there’s something where the personal and the collective are coming together. Personal grief and planetary grief are very strong in these times because we experience so many losses at a collective level through ecosystems collapsing and wars again expanding. So I felt the need to address the grief I could feel in my gut biome, but also in the collective field.

So, how could we develop practices that are nonverbal, through the body? And when I started this project, I felt there was a lot of support. And the support came for me mostly from the plant realm, maybe also because I'm a gardener. I’m not formally trained as a gardener, but I’m always gardening. We have a big garden in Berlin, and it’s something I’ve always been doing. This project, ‘Transitional Momentum for Ecological Grief,’ is the continuation of a research project I did last year for which I received funding for half a year. I did research with the title ‘Relational practices of bodies and land’ and compared our different ways of relating between dance and gardening. And at the end of this practice, I realized that because of the drought, especially in Europe, it was very hot.

Oh, yes, the drought.

I realized how much we were struggling in our garden collective. We had a lot of conversations about water and how to deal with it. And we were very busy with the vegetables. And then, one day, we realized that actually one of the largest trees in our garden, a big pine tree, was about to die. The groundwater was sinking so that maybe the tree’s roots could not reach the groundwater anymore. I felt such a sense of loss that this huge pine tree was going to die while I had just been busy with the small vegetables. Then, I realized that this tree was dying. I felt that my nervous system was in a state of fight or flight towards climate change, and I wanted to resist the change that was happening. I had a kind of personal collapse.

Did you find any sense of relief from that during this time?

Yes, well, I cried a lot when I saw this tree dying. And I had the feeling that my nervous system was actually releasing. So what happens if, on the level of the nervous system, we start to surrender instead of resisting change? And I think what happens when we recognize climate transition is that we can induce positive change, but I feel there’s a point where we need to surrender. And for me, that’s when I came in contact with grief and I think this grief is part of this surrendering process.

Yeah, that’s very powerful. I really resonate, and I really appreciate you also having the clarity and the wisdom to be able to be both in those powerful emotions, but also to be able to step outside into the broader experience of where your process is like a microcosm of the whole. Because grief really can take us into an abyss. So now as I think about your thesis presentation in your work, you focused on this beautiful large pine tree in front of the old postern building. Can you say more about that and how you set up your installation at the Postern to help people move through ecological grief?

I feel the project started much earlier. I don’t know if the project started when I was two or three years old and experienced a significant loss, or with the pine tree one year ago in my garden in Berlin. But then this creation process started three months ago where I felt like, okay, I have all this research and these different experiences, and how could it now materialize and come into form for some kind of workshop format or a facilitated space where I invite other people? I was trying to figure out where it was going to take place and who would be my collaborators. I was on the train back from Berlin to Devon when I closed my eyes and asked myself, ‘Who are my collaborators’? And then I saw an image of this pine tree in front of the old Postern that somehow is very present because it’s very tall, but it’s also a tree where we just always walk by and I didn’t really recognize it. So it was a very intuitive way of asking for support and receiving it. I think this was also a part of the facilitation of working with imagination as a creative faculty, using visualizations and intuitive ways of knowledge-making.

There is a unique pedagogy that has been developed at Schumacher of somatic work, experiential learning, place-based learning. How important was learning to you? You mentioned intuitive ways of knowing. Can you say more about that, what that means?

I think I learned the most from plants during those nine months and from my classmates. So I feel I was really recognizing nature as a teacher. And I also think that at times when I felt a bit limited by the university framework, it really helped me shift my perspective that what I’m learning here is much more. I also think that our own bodies are our biggest teachers. I think, especially in trauma work or work that is connected to healing processes, we need to provide a space where we can listen to our body. I feel like nature and the body are our teachers.

And you were asking me about pedagogy?

Yes I was wondering if you were interested in finding ways to extend this type of embodied learning with others as a new pedagogy. For example,

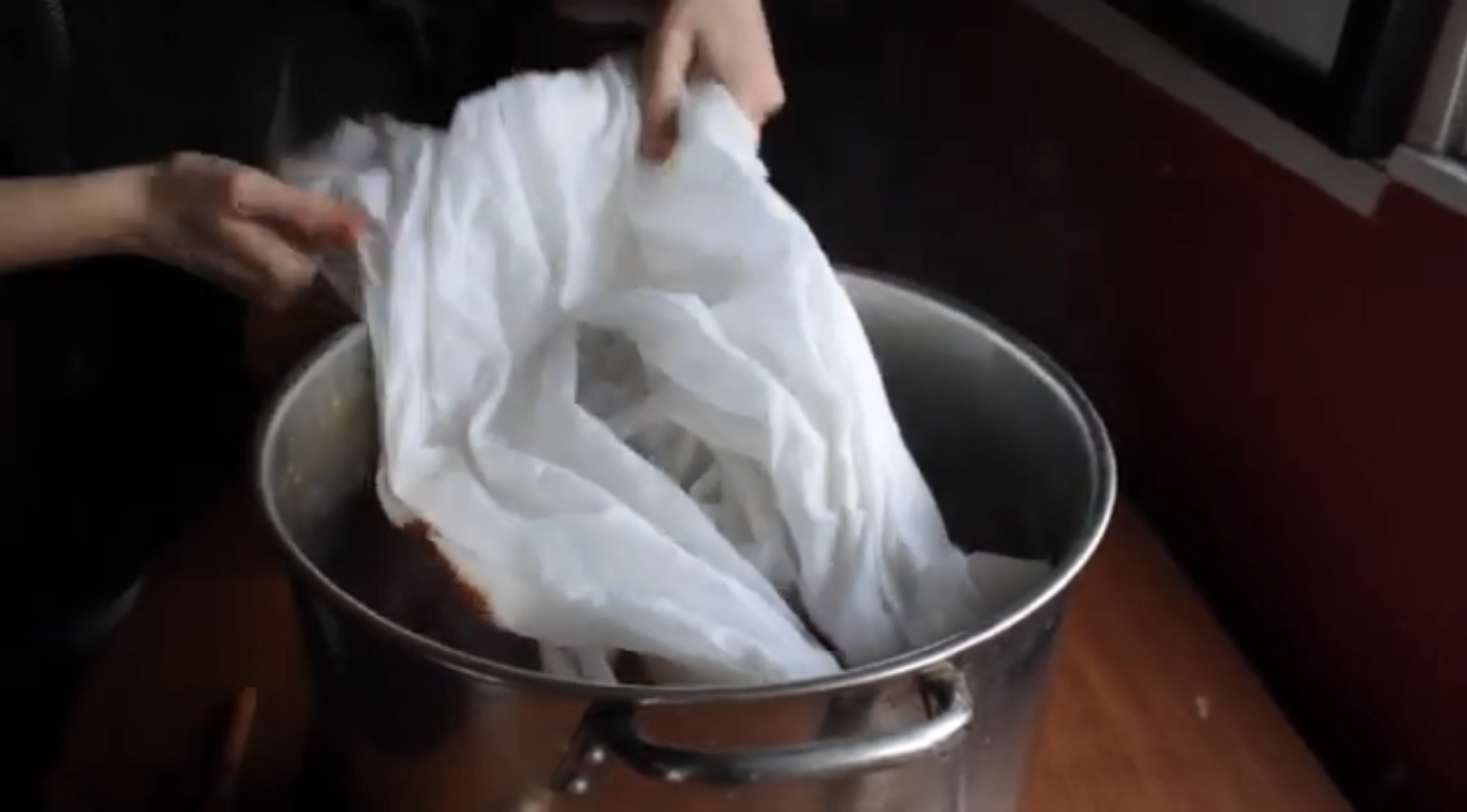

could we talk about your onion fabric installation? I was deeply moved by that on multiple levels. The way that onion skins were used and then the way that the fabric wrapped around so that I could feel safe and healthy and that I could cry. The prompt or the offering in the booklet was about women getting together after the trauma of World War II to cut onions and cry. Can you say more about that?

It's actually a story that is more fictional, but it could have happened this way. Maybe it even did happen. So I was also playing with storytelling as a modality for healing trauma. Because in Germany, we have a lot of guilt and shame still in our family lineages, and people just didn't speak about their grief and relation to the war. So there's a book by Gunter Grass Die Blechtrommel (The Tin Drum) where he's writing about these meetings of people gathering and cutting onions together in order to cry.

I think in the workshops themselves I see myself more as a facilitator or curator of the space, like a space-holder. I think what I would love to develop further is maybe this co-learning through tending with the memory cards, for example, when we had verbal grief. I think there’s something that happens through empathy. If somebody shares something and I resonate with it, then it’s already healing something in myself. So this is how actually there can be some agency to the group and the group starts to hold space for each other. So I think in the future I would love to emphasize this even more. Having these plant companions means that each person was on a journey and really did not feel alone in whatever processes they were in, with grief or exploring love or joy. This is also like getting inspired by each other. And I would love to consider these workshops also as a toolbox that other people can take this toolbox and share it somewhere else, maybe by honoring or quoting the work. It could become like a toolbox that can travel. I think this is something I learned in Schumacher College: how we bounce ideas around and that people are not that precious about their authorship.

In the art scene or in the dance scene, sometimes there’s so much more competition and people almost don’t share their ideas. And this is something I really appreciate here, that people are like, please take my song and sing it somewhere else.

Like the way that the plants do. But you’ve just offered a segue into my next question, which is what your journey has been, your education, that led you to Schumacher. I would love to hear how you became a dancer and then how that led you into this place.

Yeah, that’s very simple but also a big question. I started dancing really early, and I didn’t intend to make it a profession, but I think I just always continued dancing; it was a way of expressing myself. There were also points in my life where I wasn’t really trusting language as an expression and where I think I was always coming back to movement or body language as something that I trusted more. But I wouldn’t only define myself as a dancer. I think being a shiatsu practitioner became really important.

And I experienced great healing from the shiatsu session that you gave to me. And actually today, in honor of that, if I just may say, I have a little plant companion, which I don’t know if you can see, is a piece of Greek basil that smells so incredible. And it seems like it’s providing even more of its beautiful scent cloud now that we’re talking about it.

Basil is such a great plant. We should read more about basil. I think basil is quite a sacred plant.

And on that note, I would love to hear more about how plants and gardening influenced your journey to Schumacher.

I was always gardening. But before, I didn't consciously link dancing and gardening. It's only last year that I started to realize how much my gardening is informing my dance and art-making. It was through a friend that I heard about someone studying holistic sciences here. And then it was still quite a journey. It took me almost two and a half years to get here to raise the necessary funds and find ways with the visa. I think you can understand this as we were both international students.

Yes, for me, coming to school here was not easy and it became like a pilgrimage destination that was part of a complex journey to make it happen.

And a funny thing happened just a few days before I left for England, I was in my garden in Berlin. There's a little cottage in the garden where other people have also been gardening before. And I just pulled out a piece of paper because I needed something to make a little note. Then the paper was actually a seed bill from Dartington. Someone in my garden in Berlin, possibly, I think, seven years ago, had ordered seeds from this area here in Dartington. And I was realizing, oh, my God, there were seeds from this area in Devon that were sown in my garden in Germany. Yeah, and the plants were still there. They were herbs— I think it was oregano. Then I was like, okay, I really meant to do this. And I also realized how places are connected through plants.

Stills from film of Frederike’s MME Thesis by photographer/filmmaker Kylan Casey

Frederike’s onion fabric installation was a reference to Gunter Grasse’s storytelling imagining a community’s response to addressing unspeakable grief in his work, Die Blechtrommel.